[I did a bit of research on racism and improving diversity in golf in Oregon, and ended up with too much information to put in one article. In this article, first of two parts, I provide a brief history of racism in golf and racism in Oregon and how that is reflected in the lack of Black golfers in Oregon. The next installment (in early January), will focus on programs that are helping to expand the diversity of golf in Oregon.]

On April 26, 1974, after Lee Elder became the first Black golfer to be invited to the Masters, Carl T. Rowan wrote an opinion piece in The Oregonian on why there were not more Black golfers. Mr. Rowan stated, in part:

“But for golf, you need special courses that spread over acres of costly land. It means access to country clubs, and that means bucking the most pernicious of social snobberies as well as deeply institutionalized racism. It is a yet a wonder that a black American has worked his way into the Masters.”

Institutionalized racism in golf? Of course. You don’t have to go back to the days of golf’s invention and spread by the British Empire. Overt discrimination in golf did not end until fairly recently. For example, in 1934 the PGA adopted a “Caucasian-only” clause stating that its membership was only “for members of the Caucasian race,” which was not removed until 1961. During this period and beyond, almost all private courses remained closed to people of color, and at least until the 1950s (after the U.S. Supreme Court in Holmes v. City of Atlanta signaled that you can’t have restricted tee times for Black golfers on muni courses), many muni courses were as well or had very limited tee times. Even clubs at public courses openly excluded people of color well into the 1960s. It wasn’t until 1990 that the PGA stopped playing at courses that overtly banned Black members (taking on Shoal Creek Country Club). [For a more in-depth and better written review of racism in golf, I suggest reading Game of Privilege, Lane Demas (2017) or Uneven Lies, Pete McDaniel (2000).]

Institutionalized racism in Oregon? Of course. Although this

beautiful state is not in the Deep South, Oregon was founded as a White Homeland. In 1844, the Territory outlawed slavery, but in 1849, the Territory enacted the Exclusion Act, prohibiting Blacks from moving to Oregon. Oregon’s constitution, ratified in 1857 and effective in 1859 when Oregon became a state, provided a ban on any Black person not currently living in the State from “living, holding real estate and making contracts within” Oregon. That provision of the Oregon constitution was not repealed until 2001, despite repeated attempts to do so. In between, there were continuous overt displays of racism in Oregon, including the election in 1922 of a member of the KKK, Walter Pierce, as governor. In more recent times, urban modernization/beautification projects have destroyed entire neighborhoods of Black folk (the 1956 project for Memorial Coliseum in Portland where one goal was a “white corridor” between downtown and the Lloyds Center; the 1970 expansion of Emanuel Hospital in Portland; and the continuing gentrification in residential neighborhoods). There were also the 1960s and 70s busing laws where only Black children were bused, the continued reliance on a non-unanimous jury verdicts in criminal cases (although aimed at immigrants, the overall goal was to overcome people “untrained in the jury system”), and, presently, the disproportionate amount of COVID illnesses and deaths in nonwhite populations in Oregon.

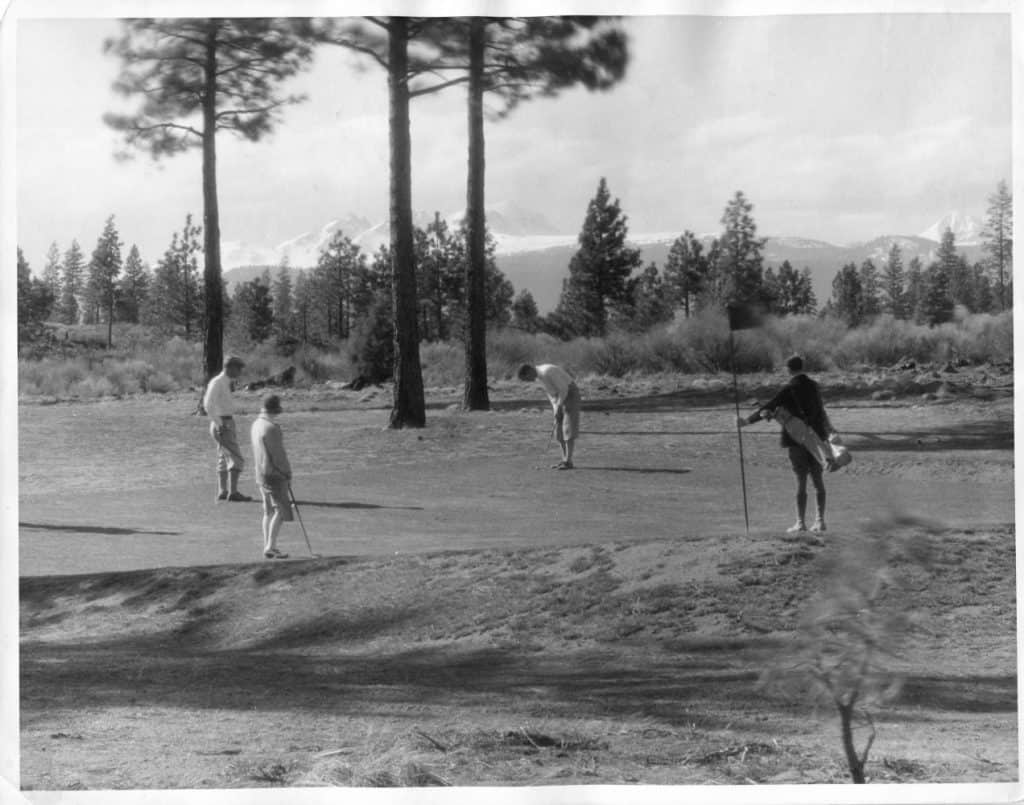

Blacks may have been able to play at some public courses in

Oregon, but they were, by decree or practice, excluded from being members of golfing clubs or country clubs, or participating in tournaments until at least the 1960s. While most private clubs in Oregon did not have stated prohibitions against Black members, exclusionary practices persisted. By 1990, less than half of the private courses in the Portland metro area had a Black member. In an August 5, 1990, article in The Oregonian, it was suggested that barriers for possible Black members included the cost to join and the need to be nominated by an existing member. Charles Ganter, the then president of Leisure Hour Golf Club (more on the club below) stated “I would not say its economic. A lot of our own members can afford it. . . . They [the country clubs] tend to say there’s no problems, no barriers. But if you look back at history, there are problems, there are barriers.” Leon McKenzie, Jr., a golfer and track coach at Benson High School, suggested that it was simply a continuation of the discrimination that existed throughout Oregon, “If you live in Oregon, you deal with it at all times. . . . There’s only a 4 percent Black population in Oregon. It’s something you live with every day.”

With massive suppression of Black golfers by Golf (meaning clubs, organizations, and players) and of Blacks by Oregon (meaning the state and its people), it would seem highly unlikely to historically find any Black golfers in Oregon. But the strong allure of the game and the determination by some folks provided otherwise. Mr. Demas in Game of Privilege reports that in the 1910s, members of the primarily Black AME Church in Portland regularly played golf with their pastor. Leisure Hour Golf Club was founded in 1943 by Vernon Gaskin (a former caddy at Waverley), Stephen Wright, Walter and Gladys Risks, and Shelby Golden (formerly on the University of Oregon golf team) to have a place to socialize and play golf tournaments (because they were not allowed in men’s or women’s golf clubs). In 1944, the club held its first tournament at Eastmoreland, which hosted until 1948 when the venue switched to Tualatin. (The club now plays out of Glendoveer and has about 70 members of all races.) In 1943, Mr. Gaskin also helped found the Western States Golf Association, an association of non-discriminatory golf clubs based mainly in the west, with Leisure Hour as a member. (In 1958, Western States held its Championship at Glendoveer and in 2015 at Heron Lakes, Rose City, and Stone Creek.)

As an historical aside, Oregon municipal golf courses provided assistance to the first Black golfer to win any USGA event. William Wright, Steven Wright’s nephew, initially grew up in Portland (where he was introduced to the game) and then moved to Seattle. In Seattle, he was barred from joining any club, so he could not establish a handicap. He then came to Portland where he was able to establish a handicap at Eastmoreland, and then was able to compete in USGA events. In 1959 he won the US Amateur Public Links Championship. (After winning the Public Links, Mr. Wright tried to go pro but was unable to obtain any sponsors.)

With overt discriminatory practices fizzling out in the 1990s and the rise of Tiger Woods, is there still discrimination in golf? There are lots of opinion pieces on this (the vast majority answering “yes”). Continued problems within the PGA are discussed in the November 13, 2020, article in Daily Cover – Sports Illustrated, “What Golf’s Race Problem Looks Like from the Inside” by Jenny Vrentas. But for now, let’s just look at the numbers.

Unfortunately, we do not know the percentage of Black golfers (or even nonwhite golfers) in Oregon. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that as of 2019, approximately 25 percent of the population in Oregon was nonwhite, with 6.2 percent being Black (including mixed race, which may not include people who are Black at all). The only study I have found on diversity in golf in Oregon is a 2019 self-reporting online survey of golfers (who mostly booked tee-times online, so there may be some accuracy issues through self-selection) by Portland Parks & Recreation. In that study, 10 percent responded that they were nonwhite and 2 percent responded that they were Black. Anecdotally, in 2001, when there was a surge in popularity in golf attributed to Tiger Woods, Steve Duin of The Oregonian spoke with pros at several public courses in Portland and found that there was very little diversity in new junior golfers (e.g., RedTail reported only 5 nonwhite participants out of 450 kids at its golf camp).

Nationally, according to estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, approximately 40 percent of the US population is nonwhite with about 16 percent being Black or mixed race. The National Golf Foundation (“NGF”) in 2003 estimated that there were 27 million golfers of which approximately 14 percent were nonwhite and 5 percent were Black. In 2006 NGF reported 23.6 million golfers of which 4.6 million (or about 19 percent) were nonwhite (so a little up-tick when the popularity of golf was declining after the rise of Tiger). In 2017, the PGA estimated that 18 percent of golfers were nonwhite (so no change over a decade) and that the number of Black Associates with the PGA was about ½ of a percent.

From the information that is available (as well as simply noticing

when you play or practice), persons of color (including Blacks) are significantly underrepresented on golf courses in Oregon (as well as nationally). [Here, I could discuss “should Golf care,” but I hope that would be self-evident: from improving the overall financial condition of the industry through increasing players, to being good golfers and welcoming, respecting, and supporting everyone who wants to play.]

In the next installment, I will discuss probable continued barriers in golf preventing an increase in the number of Black golfers in Oregon, and programs that are working to overcome those barriers. In the meantime, please provide any comments to [email protected]